The "Lost Cause" and the "Antebellum Imagination "

In my Introduction to History course this semester, I am trying to teach students to understand the concept of “historical memory” and how it functions in everyday life. In this selection from a module which teaches them about the concept of the “Lost Cause,” I try to help them better understand the overt and subtle ways in which the myth of the “Lost Cause” is embedded in the contemporary cultural milieu. In this section, I have them focus on the “antebellum imagination”—a way of thinking that effaces the history of enslavement and violence and instead imagines a glorious period of great houses, refined manners, and fancy dress.

The sections below look at the history of film, of marketing, and popular culture. It addresses Barbie, “plantation weddings,” and the marketing of “Aunt Jemima.” I have included a short demonstration of how a Wikipedia entry serves the myth of the “Lost Cause” (and I update the entry to better reflect historical facts).

Please feel free to borrow from this material for your own courses.

In the wake of the Civil War, the advocates of the"Lost Cause" myth used public commemoration and monument-making to help spread their ideas--ideas that attempted to soften and ignore the violence of slavery and white supremacy in the United States. This myth-making process has continued to take place through to the present day--and monuments, while profoundly symbolic, are only one facet of the much broader cultural imagery used to bolster the "Lost Cause."

It is rare that the "Lost Cause" is evoked directly in contemporary media and speech. Nevertheless, the myth is there if we know where to look. One of the places that we see the "Lost Cause" narrative is in storytelling and marketing associated with the "antebellum" South. "Ante-," meaning before, and "-bellum," meaning war, is an adjective often used to describe the southern United States before the Civil War. While it refers to a period of horrific human rights abuses, the effects of propaganda about the South and the Confederacy in the wake of the Civil War has generated a mythology that imagines a glorious period of great houses, refined manners, and fancy dress.

We have all seen versions of what we might call the "Antebellum Imagination"--of "Southern Belles' and dashing gentlemen in suits and classical buildings and magnolia trees. They live lives of leisure, as we see in this still from Gone with the Wind. When enslaved labor is portrayed, it generally avoids referencing the daily violence on which the system rested--not to mention the fact that very few southerners had such wealth.

Still from Gone with the Wind

The "Antebellum Imagination" is a type of historical memory that gets sold to us through consumer items and media to the point that many of us never think about it. The romanticization of the South had precedents before the Civil War, but it was after the war that the "Antebellum Imagination" took off, driven in large part by myths associated with the "Lost Cause." In the readings and videos that follow, we will look at a few--though, by no means, all--of the ways in which the "Lost Cause" has been reproduced through the "Antebellum Imagination" over the last century.

Vintage Barbie Plantation Belle #966 (left) was produced between 1959 and 1961 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. It hearkened back to plantation life, 100 years before. In 2004, this Barbie was reintroduced as the Plantation Belle™ Barbie® Doll (right).

Film and the "Lost Cause"

One of the most powerful "Lost Cause" cultural products was D.W. Griffith's film, Birth of a Nation, released in 1915. It was effectively a propagandistic re-write of the previous 50 years of US history. It imagined a peaceful and prosperous "antebellum" period, which was destroyed by giving rights to African Americans. In this story, the KKK is a heroic force, reasserting white supremacy. It was wildly popular among white audiences of the period. Watch this short, 5-minute summary of the film and its impact: https://pbslearningmedia.org/resource/reconstruction-propaganda/reconstruction-the-birth-of-a-nation-rewriting-history-through-propaganda/support-materials/

The "Lost Cause" narrative was reproduced by Hollywood in film-after-film, perhaps most notably in Gone with the Wind from 1939. Film scholar Jacqueline Stewart contextualizes the film in this introduction for TCM:

Racist Iconography and the Antebellum Imagination in Film

While the "Lost Cause" myth attempts to reshape historical memory by appealing to a re-Civil War (antebellum) past that never was, it included a series of racist cultural tropes into this mythology. As you watch this video, pay attention to the ways in which you see these stereotypes in your day-to-day experience.

Plantation Tourism

Another example of "Lost Cause" cultural production is what we call "plantation tourism." "Plantation tourism" is a mode of cultural production that markets the houses and estates of the nineteenth-century South as markers of sophistication and tranquility. Over the late 20th- and early 21st-century, the plantations of the south reproduced the myths of the "Lost Cause," targeting tourists who were infatuated with the stories told by films such as Gone with the Wind.

The owners of the plantation estates do things such as market to wedding parties that wish to use the houses and grounds of these estates as wedding backdrops. In fact, in recent years, there has been a whole sub-genre of wedding called "plantation weddings." To get a sense of this sub-genre, see the wedding website The Knot's story "Going Beyond Gorgeous: 4 Undeniable Reasons to Plan a Plantation Wedding."

In recent years, some of those involved in the plantation tourism industry have begun engaging with broader histories and have integrated historic interpretations of slavery into their stories--to a greater or lesser extent. Nevertheless, for many properties, the "Antebellum Imagination" is hard at work. Take, for example, this advertising video for Belle Meade Plantation in Nashville, TN. As you watch, ask yourself, what kinds of memories are the owners trying to evoke about the plantation? How is the video articulating ideas about history and race? How is historical memory framing the tone of the video? What do the images suggest about the plantation--both its past and its present?

Plantation Tourism and the Media: The Entry for Wikipedia's Rosedown Plantation

Plantation tourism that promotes antebellum luxury and grace à la Gone with Wind effaces the history of slavery and the role that plantations played in the institution of slavery and white supremacy in this country. This imagined world of the antebellum South doesn't end with plantation tours. It's reproduced in all kinds of media.

In the video below, I provide an example of the Wikipedia entry for "Rosedown Plantation" as it existed on 22 August 2020. Watch it to see how the myth of the "Lost Cause" can be subtly reproduced in through the ways in which writers phrase the histories they tell.

Marketing the Plantation

Yet another example of the extent to which plantations help imagine the "Lost Cause" is through its use in marketing. Drawing on popular media representations of the antebellum South, numerous organizations have used the plantation to sell products over the past 150 years.

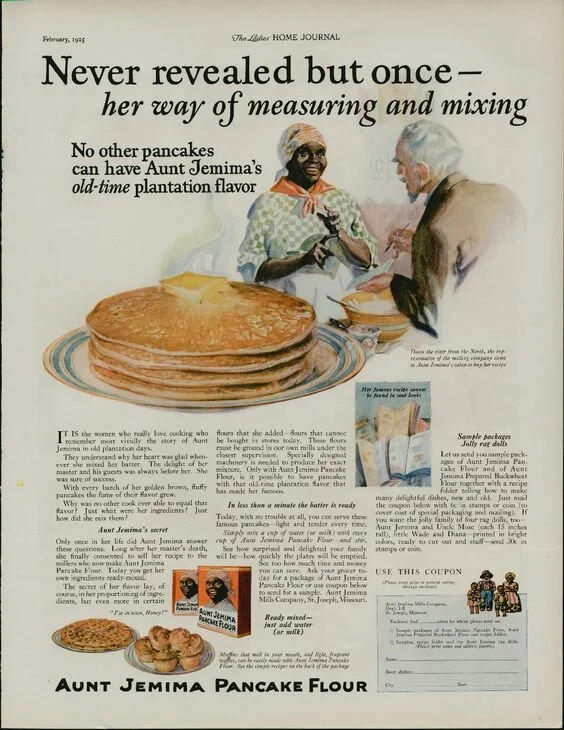

This advertisement from 1925 in The Ladies Home Journal creates a narrative for "Aunt Jemima." Invoking "old-time plantation flavor," it was overt in its messaging that the relationships between slaveholders and enslaved individuals were friendly and that life on the plantation was fulfilling

"It is the women who really love cooking who remember most vividly the story of Aunt Jemima in old plantation days.

They understand why her heart was glad whenever she mixed her batter. The delight of her master and his guests was always before her. Se was sure of success."

The coupon at the bottom of the page reinforced this narrative. Buyers could send away for rag dolls representing an enslaved family: "Aunt Jemima and Uncle Mose (each 15 inches tall), little Wade and Diana." A family of enslaved individuals for children to play with--60 years after the end of the Civil War.

In fact, it's in cooking where we see a huge amount of marketing that uses antebellum myths of the plantation. And, these marketing campaigns continue through to the present day. Take, for instance, Carolina Plantation rice products, the website of which implies that their products are somehow more authentic. We learn on their website that "Carolina Plantation Rice comes to you from the only colonial plantation in the Carolinas to grow rice for commercial sale: Plumfield Plantation on the Great Pee Dee River."

The Carolina Plantation tagline is "A Taste with a History." What is this history? Well, there is a "Rice History" page on the website. The history they tell is about the rice. Only once is the history of enslaved labor discussed on the page--and then, only obliquely: "Rice remained a dominant commodity on the coastal rivers of South Carolina until the end of the Civil War, when production started a long decline due to a loss of labor and working capital, and aided by several severe storms. In the early 1900's rice farming disappeared from the state all together. Rice was never grown as a cash crop in the Darlington area where Plumfield Plantation now produces Carolina Plantation Rice, but it was grown there in small plots by slaves who raised it for their own consumption, as they had traditionally in Africa."

Of course, there are plenty of other products that use "plantation" in their labeling to invoke historical memories of antebellum tranquility and prosperity. Here are examples of a few of them.

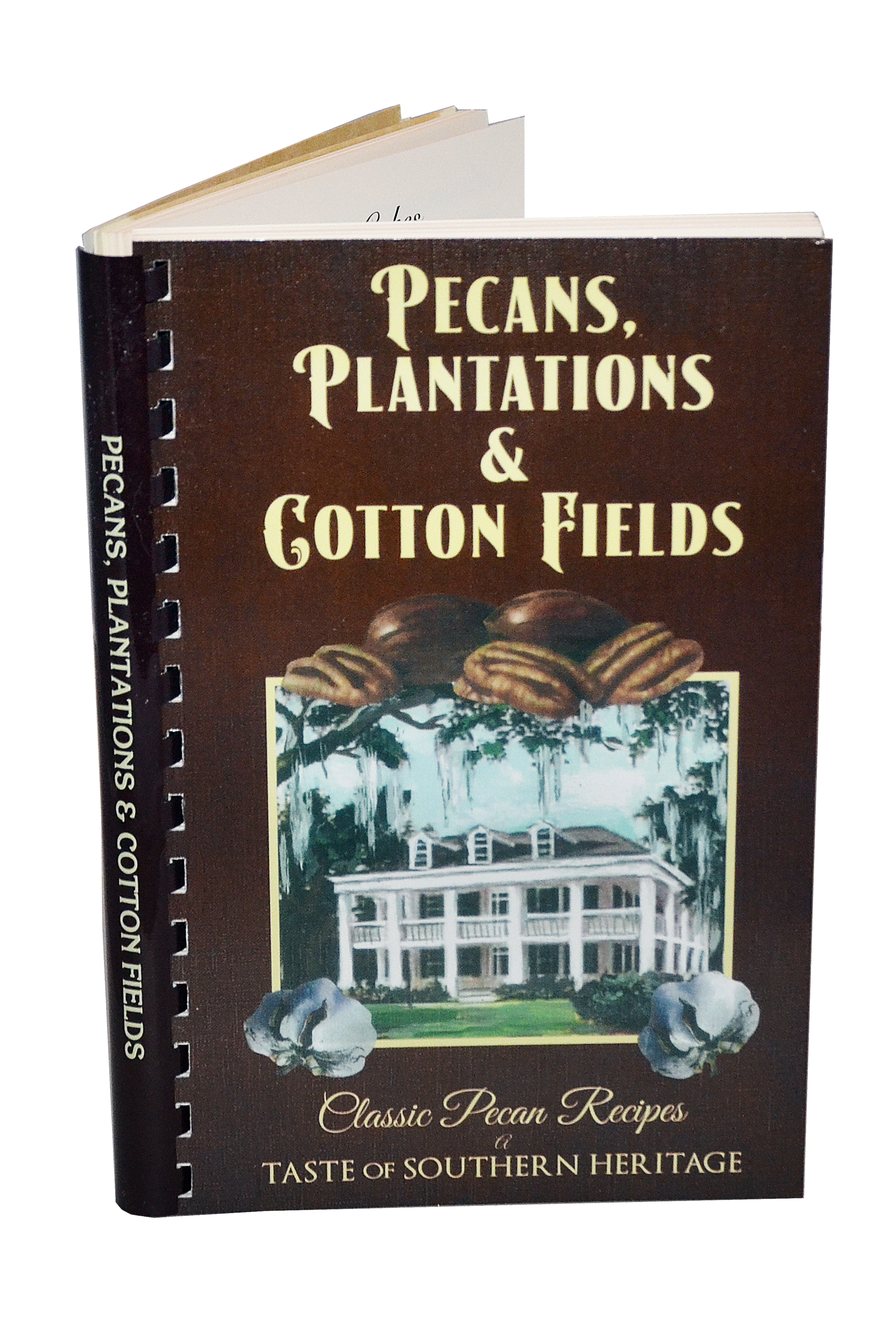

Using the plantation as a stand-in for myths about the antebellum South are quite prominent in cookbooks. Here is a good example:

The reviews of the book are revealing for the emotions that the book is meant to evoke. A review on the book on eBay from 2010 reflects its tone: "Beautiful Southern settings with equally appealling [sic] recipes. This is a well written 'walk down memory lane' from Lee Bailey's vantage." On Amazon.com, a reviewer states that "Having lived in Georgia for awhile I know a "good ol' boy (Links to an external site.)" when I see one! Lee Bailey, a true Southern gentleman, makes it all look so easy."

There are dozens and dozens of cookbooks that romanticize the antebellum South and thus help reinforce the myths associated with the "Lost Cause." Here are a few examples.