Slavery and Race in Frankenstein

A version of this essay was originally published as Jason M. Kelly, “Slavery and Race in Frankenstein,” Indiana Humanities One State / One Story: Community Read Program Guide, version 5 (20 March 2018), http://quantumleap.indianahumanities.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Frankenstein_PG_V.5-1.pdf.

Villa Diodati is the house that Byron and Polidari rented in the summer of 1816 and the location where Mary Godwin (later Shelley) composed Frankenstein. It is located along Lake Geneva in the town of Cologny, Switzerland.

Switzerland. 1816. Despite the wet days and stormy nights on Lake Geneva, Lord Byron, John Polidari, Mary Godwin [later Shelley], Percy Bysshe Shelley and Claire Clairmont enjoyed the weeks they spent together. Boating, walking, writing, conversing . . . they lived a life of privilege that summer. By the middle of June, the group was composing the stories that would make their holiday famous. Telling tales of vampires, reanimated corpses, and ghost tales was just another way to amuse themselves.

To the modern reader, these stories often appear far removed from reality, but the fictions the authors created were deeply rooted in the concerns of the day. Mary Godwin’s Frankenstein, for example, was tied to debates in natural philosophy. Her readers would have easily recognized the links that she was making to contemporary experiments in chemistry and galvanism—and to the psychological theories of Locke and Rousseau. These stories reflected contemporary social and political concerns as well, including anxieties over and race, which was a key theme in Godwin’s story Frankenstein.

***

Mary Godwin was the child of two famous radicals, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, known for their critiques of the contemporary social system. Percy Shelley, the man whom she would marry later that year, was himself a radical. In the years before their trip to Switzerland, he had published numerous critiques of religion and social inequity. As radicals and reformers, Mary, her family, and her friends were engaged in many of the pressing social issues of the day. Among these was the issue of slavery.

For centuries, the country of their birth, Britain, had been one of the key participants in the Atlantic slave trade. Along with other European states, such as France and Spain, Britain had forced nearly 12 million Africans into slavery. As these empires conquered territories in the Americas, they cleared land to grow cash crops—tobacco, sugar, cotton, indigo—worked by enslaved populations. The profits from this forced labor helped build new systems of finance and provided capital to drive the Industrial Revolution.

While enslaved individuals had long fought for their freedom, their plight was ignored by British religious leaders, politicians, and intellectuals. Only in the late eighteenth century did the issue of slavery become a political issue for European reformers. A series of high profile court cases exposed the horrors of slave trade, sparking a broad movement for abolition in Britain. In 1807, the British government bent to political pressure and banned the transatlantic slave trade. But, planters in the colonies were still legally permitted to own slaves.

Both Mary and Percy wanted to see an end to the institution of slavery. Throughout their lives, they had read the perennial Parliamentary debates between abolitionists and planters. They learned about the horrors of the Middle Passage—of the millions who had died on slave ships—and the millions more who had been forced into grueling and dangerous labor in mines and sugar and cotton plantations in the Americas. In 1812, Percy critiqued the morally corrupt system of slavery in his poem “Queen Mab”:

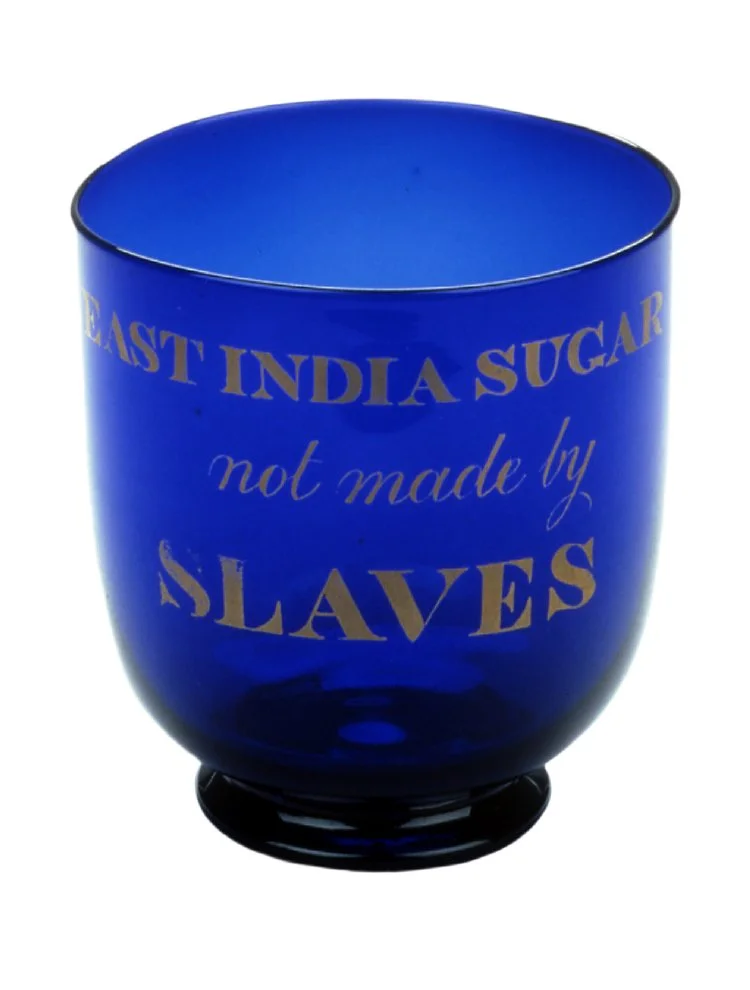

"Blue glass sugar bowl inscribed in gilt 'EAST INDIA SUGAR/not made by/SLAVES'". ca. 1820-1830. Bristol. Height: 110 mm; Diameter: 100 mm. British Museum Department of Britain, Europe, and Prehistory. 2002,0904.1.

[Humanity] was bartered for the fame of power,

Which, all internal impulses destroying,

Makes human an article of trade;

Or he was changed with Christians for their gold,

And dragged to distant isles, where to the sound

Of the flesh-mangling scourge, he does the work

Of all-polluting luxury and wealth . . .

Slavery and the slave trade transformed Britain. By the eighteenth century, it permeated every facet of daily life—from the ways that Britons thought about human nature to the consumer goods that they purchased. For example, as the largest market for slave-produced sugar in the world, Britons had a reminder of their culpability in the slave trade every time they took their tea. In response, some consumers boycotted sugar from the West Indies, purchasing sugar labelled as “not made by slaves.” Like some other reformers, both Mary and Percy abstained from sugar in their tea altogether, a form of protest meant to distance themselves from institution of slavery.

***

One of the most insidious effects of the slave trade was the development of the early modern concept of race in order to justify the institution of slavery. To do this, Europeans turned to the sources of authority that they knew best. Some attempted to support the practice of slavery and racial difference by using excerpts from the Christian scriptures. Others turned to natural philosophy—what we now call science. There were dozens of variations to their justifications, but they boiled down to the essential point that Africans were somehow fundamentally different from Europeans. Their arguments allowed Europeans imagine that they had the right to treat other human beings as commodities. Even as governments slowly dismantled the system of slavery, racist ideology remained. Racism was a useful tool to Europeans—in their minds, justifying continued imperialism, inequality, and exploitation.

Mary Godwin’s and Percy Shelley’s world was infused with this racism. From visual art to literature to theater to music, ideas about race saturated their cultural environment. The newspapers regularly spit out racist opinions. And, the British empire’s political and economic policies—even its legal system—served to maintain a system of supremacy that increasingly hinged on notions of racial hierarchy.

Natural philosophy was particularly susceptible to this racialized atmosphere. Philosophers brought many of their cultural preconceptions and biases to their research, including assumptions about race. Rather than challenge racist ideology, writers built new theories to justify racist concepts. By the late eighteenth century this meant linking physiological differences to intellectual and moral capacities. Claiming that their arguments were based on observations of the natural world and natural laws, their work provided a philosophical foundation for race-based hierarchies.

Despite their reformist attitudes, Mary and Percy were nevertheless products of their age. Being abolitionists did not make them immune to racial assumptions. And, in fact, Mary Shelley’s fascination with natural philosophy led her to integrate early nineteenth-century ideas about race into the text of Frankenstein. She used race as a signifier of terror, hinting that Frankenstein’s Creature was another race—powerful and revengeful—running amok and threatening the safety of Europeans.

***

Godwin’s understanding of race came from a variety of sources. Among these was the Comte de Volney, who in 1791 published Ruins, or Meditations on the Revolutions of Empires (Les Ruines, ou méditations sur les révolutions des empires)—a text focused on examining the causes of the rise and fall of empires. Volney’s work was extremely popular, and Thomas Jefferson even translated a large portion of the text.

In Frankenstein, the Creature explicitly cites Volney’s book. He claims that it gave him “insight into the manners, governments, and religions of the different nations of the earth.” But, it also gives him an introduction into how Europeans expressed racial difference:

I heard of the slothful Asiatics; of the stupendous genius and mental activity of the Grecians; of the wars and wonderful virtue of the early Romans—of their subsequent degeneration—of the decline of that mighty empire; of chivalry, Christianity, and kings.

Racial difference was almost always expressed in moral and intellectual terms. In this case, those of Asian descent are imagined as “slothful,” a common trope in early modern Europe. On the other hand, the Greeks, Romans, and Medieval Europeans are notable for their “genius,” “mental activity,” “virtue,” and “chivalry.”

Godwin’s text was suffused with racial allusions that were central to contemporary natural philosophy. Like so many of her contemporaries, she repeatedly emphasized the importance of skin color. For example, when Victor Frankenstein first makes the Creature, she writes that

His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion, and straight black lips.

In contrast, Godwin notes the paleness of Victor, Caroline, and Elizabeth’s skin, both in life and in death.

Godwin’s description of skin color was not simply a descriptive device. For her and her contemporaries, skin color was a defining outward marker of racial difference. This was the case, for example, with the natural philosopher Johann Friedrich Blumenbach who argued that there were five varieties of humankind: Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. For him, the Caucasian was the original race, and the others had “degenerated” from it due to variations in climate or diet. Other writers argued for four or six, but there was a consistency to all of their arguments: racial difference was a fact that could be supported through empirical evidence.

As they had classified animals, natural philosophers believed they could classify human variation. Some people, such as Blumenbach, argued that despite their differences, humans were fundamentally the same species—that they had descended from a common ancestor. These people were known as monogenesists. Others, such as Lord Kames and Charles White, argued that each group was fundamentally distinct, and that each race of humans had a unique creation. These people were known as polygenesists. Both groups, despite their differences in describing the origins of human types, nevertheless imagined a hierarchy of races. And, this hierarchy inevitably featured Europeans—imagined as “Caucasians”—at the top.

Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley had a more-than-passing familiarity with theories of race. Not only were they deeply engaged with debates in the natural philosophy community, their physician and friend, William Lawrence, was a popularizer of Blumenbach’s theories. Consequently, when Godwin described the Creature’s skin as yellow, she could expect that audiences would read it as an indicator of race. This was a perspective that she underlined by consistently emphasizing the ugliness of the Creature—a common theme in the literature on race that emphasized the superior beauty of “Caucasians.”

***

In many ways, Godwin used Frankenstein’s Creature as a stand-in for European anxieties about those they had enslaved in their colonies. In the weeks leading up to composing Frankenstein, she would have learned about the Easter 1816 uprising on Barbados, organized by an individual named Bussa. It was one of the largest revolutions ever in the British Caribbean. Godwin and her contemporaries would have compared it to the successful revolution begun in Haiti in 1791—a violent, protracted war that ended in independence for Haiti, France’s most important sugar colony.

Frankenstein played on British fears of uprisings and violence—especially those perpetrated by supposedly inferior races in the American colonies. When the Creature asks Victor for a mate so that they can “go to the vast wilds of South America,” Victor sympathizes with him. But, he rebuffs the Creature out of fear that the Creature lacks self control:

You will return, and again seek their kindness, and you will meet with their detestation; your evil passions will be renewed, and you will then have a companion to aid you in the task of destruction.

Victor ultimately decides not to make a mate for the creature, because he worries they might create a race that would rise up and destroy humanity.

***

In effect, Godwin’s book both reflects and contributes to broader concerns about race and slavery in early nineteenth-century Britain. For her contemporary readers, the Creature’s monstrosity was not simply about his reanimated body or his revenge on Victor. Frankenstein also encapsulates anxieties over maintaining racialized hierarchies and fears over uprisings in the colonies that challenge white supremacy.

Bibliography

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, author. “Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism.” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1 (1985): 243–61.

H. L. Malchow, author. “Frankenstein’s Monster and Images of Race in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Past & Present, no. 139 (1993): 90–130.

Mellor, Anne K. “Frankenstein, Racial Science, and the Yellow Peril.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts23, no. 1 (2001): 1–28.

Mulvey-Roberts, Marie. Dangerous Bodies: Historicising the Gothic Corporeal. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Piper, Karen Lynnea. “Inuit Diasporas: Frankenstein and the Inuit in England.” Romanticism 13, no. 1 (2007): 63.

Smith, Allan Lloyd. “‘This Thing of Darkness’: Racial Discourse in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” Gothic Studies 6, no. 2 (2004): 208–22.