Ghosts, Satanism, and 19th-Century Tourism at West Wycombe

From Secrets of the Hellfire Club: Decades after the group ceased to meet, the stories of the Monks of Medmenham Abbey circulated in the form of rumors and gossip. And, as members of the club passed away, popular interest remained. At the turn of the nineteenth century, tourism in Britain increased, and West Wycombe became a popular destination. Not only was curiosity piqued by the famed gardens and walks of the Monks, but rumors of hauntings also fueled interest.

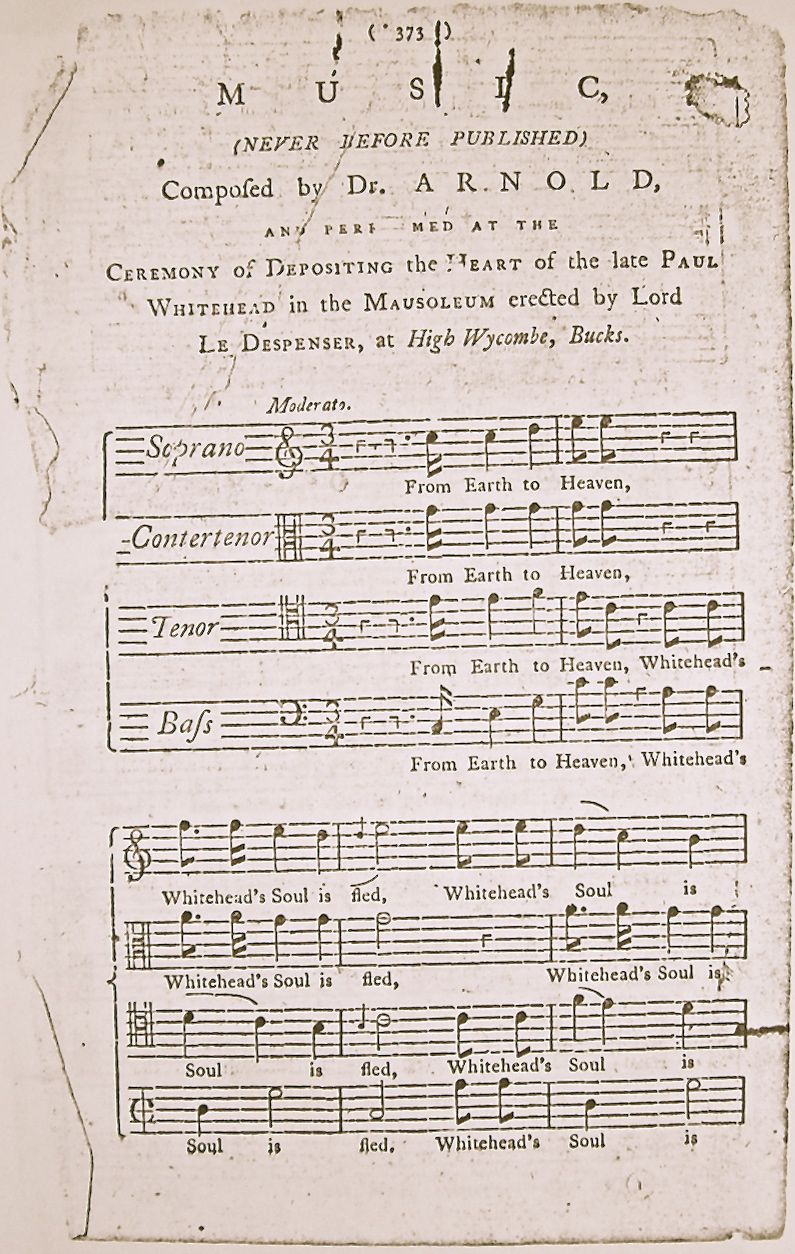

Ghost stories about West Wycombe were already in circulation in 1781 when Francis Dashwood, aged and sick, as well as servants on the estate began claiming that they had seen Paul Whitehead’s ghost in the house and gardens.[1] Paul Whitehead was a member of the abbey and rumored lover of Francis Dashwood. When Whitehead died in 1775. Dashwood built a mausoleum in his honor, holding a procession, commissioning music, and placing Whitehead’s heart in an urn in the mausoleum.

Locals soon saw the potential for profit. They led tourists to the supposed meeting sites of the Medmenham Monks – the ball at the top of the St. Lawrence Church and the West Wycombe caves, chalk tunnels which Dashwood had excavated in the 1750s to employ the local population. They told the tourists ghost stories. Visitors were even given the opportunity to hold Paul Whitehead’s heart — until it was stolen by an unnamed Australian in 1829.[2] The ghost stories became more and more popular in the nineteenth century. For example, in the 1870s, Mortimer Collins wrote that Medmenham was

Right famous for a veritable ghost; The hell-fire club at Med’nam turn’d men pale;[3]

Although he decided not to tour the caves in the 1870s, Mortimer Collins noted that any visit to the St Laurence Church of West Wycombe entailed visiting the caves, passing “an hour or two in dirt and darkness,” “the victim of a guide.”[4] Another author noted that he toured the caves in 1875, and on this visit, he also visited the golden ball at the top of the church, now covered with the autographs of visitors. He was charged 6 pence for an entry fee, and it was so popular that it brought the church £120 revenue per annum – in other words, about 4800 visitors every year.[5]

The local tour guides, who received tips from the visitors, must have been telling and retelling the story of the Monks of Medmenham with some consistency, for the stories about West Wycombe tended to be fairly consistent. Most authors noted that while the monks’ sexual appetites were excessive – and that the men had poor morality – they were not abnormal for the eighteenth century.[6] One Oxford student remembered them thus:

In Medmenham Abby they passed the day, Those jolly Abbots, ‘mid wine and lay: There Hugh le Despencer, gallant and free, Bid “fay ce que voudras” their motto be.[7]

Likewise, the men were generally represented as areligious, or agnostic, not openly atheistic.[8] The story of Whitehead and Dashwood’s romantic relationship had disappeared, even though the story had been printed with every edition of William Cowper Works during the first half of the nineteenth century. And, as they had been in the 1750s, the monks and their world were a source of curiosity. They had become part of the community’s imaginary landscape – part of its heritage – a set of stories and attractions that brought visitors to a small Georgian town along the road to Oxford.

Then, within just a few years at the turn of the 20th century, the stories about the West Wycombe landscape changed. They became more terrifying, and the topography of West Wycombe became potentially threatening. In 1894, Charles Henry Pearson made the first reference to satanic rituals at West Wycombe:

The worst acts imputed to the monks of Medmenham are, I believe, the invocation of the devil by Lord Sandwich, [and] the giving [of] the sacrament to a dog by the same worthy.[9]

In 1901, another author claimed that Medmenham was haunted by the blasphemous monks, who indulged in “beastly pleasures and beastly humors.” [10] Another author claimed that “the wraith of the last of the mad monks of Medmenham” haunted the landscape as a “homicidal ghost.”[11] Who started these more threatening versions of the area’s history is unknown, but one contemporary claimed that they were being circulated by “local mystery-mongers.”[12]

It seems that the new stories at West Wycombe and Medmenham did nevertheless contribute to the local tourist economy. And, one writer from the Times recognized the value of the mysteries and secrets of West Wycombe in an analysis in 1920:

The oldest of us never loses that part of youth which sees romance in sheer villainy. We disapprove for righteousness’ sake, but such a motto as – “Fay ce que voudras” – the very text of hedonism charms reputable persons into curiosity and ever into a shame faced sympathy . . . No one knows accurately what were the revels in this mysterious place. The proceedings were secret, but rumour said that wild rites were practiced. Satan received the crapulent homage of the pseudo-monks.[13]

While the church and caves were consistent tourist attractions in the 1920s – and, in fact, the ghost of Paul Whitehead had been joined by Sukie, the ghost of a murdered, love-scorned chambermaid from the George and Dragon Inn – the rest of the village struggled financially.[14] To save the pristine village, which Victorian aesthetics had left virtually untouched, the Royal Society of Arts, Commerce, and Manufacture purchased it in March 1929.[15] Transferring the title to the National Trust in 1934 was followed by Sir John Dashwood’s grant of the church hill and the caves in 1935 and 300 acres and an endowment in 1943.[16] The postwar years escalated the mythmaking at West Wycombe, and stories of poltergeists and villainous monks found their way into an increasingly broad array of popular culture.

[1] William Copwer to Rev. William Unwin, 24 November 1781, Works of William Cowper, vol. 2 (London, 1853), pp. 373-4.

[2] West Wycombe Park, The Dashwood Mausolem [n.d.], p. 8.

[3] Collins to T.E. Kebbel, 13 September 1872, Mortimer Collins, Mortimer Collins, His Letters and Friendships with Some Account of His Life, vol. 1, ed. Frances Collins (London, 1877), p. 113.

[4] Mortimer Collins, Pen Sketches by a Vanished Hand: From the Papers of the Late Mortimer Collins, ed. Tom Taylor (London: Richard Bentley, 1879), p. 101.

[5] Edward Verrall Lucas, Pleasure Trove (Books for Libraries Press, 1968), p. 123.

[6] Alfred Rimmer, Rambles Round Eton & Harrow, new ed. (London: Chatto & Windus, 1898), pp. 36-43.

[7] “On the Thames: A Summer Idyll,” College Rhymes, vol. 7 (Oxford, 1866), p. 147.

[8] Cf. Edward Walford, Tales of Our Great Families, vol. 2 (London, 1877), pp. 187-8.

[9] Charles Henry Pearson, National Life and Character: A Forecast (London: Macmillan, 1894), pp. 211-12 fn. 3.

[10] Justin McCarthy, History of the Four Georges, vol. 3 (New York, 1901).

[11] Eliakim Littell and Robert S. Littell, The Living Age, 7th series, vol. 18 (1903), p. 420.

[12] Charles George Harper, The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road(1905), p. 120.

[13] Times, 29 March 1920, no. 42371, p. 17, col. f.

[14] The caves were drawing thousands of visitors even in the midst of the depression in 1935. See Times, 23 July 1935, no. 47123, p. 11, col. e. Supposedly, Sir Francis Dashwood had a secret passage between the house and the George and Dragon, which the locals claimed to have partially excavated in 1963. See Times, 11 June 1963, no. 55724, p. 7, col. f.

[15] Times, 6 February 1934, no. 46671, p. 11, col. d.

[16] Times, 23 July 1935, no. 47123, p. 11, col. e; Times, 23 December 1943, no. 49736, p. 7, col. b.