Open Access and the Historical Profession

[The following is an essay that I wrote for Digital Sandbox in August 2013.] In this essay, Dr. Jason M. Kelly analyzes the American Historical Association’s recent statement on embargoing completed history PhD dissertations and provides an in-depth summary of the history of the open access movement. Dr. Kelly–an Associate Professor of British History at IUPUI as well as Director of the IUPUI Arts and Humanities Institute–challenges us to consider the ways in which digital technology offers the potential to establish new, open methods for creating scholarship, methods that hold the potential to “transform our profession.” While this essay focuses on open access within the history profession, it is an issue that all disciplines will have to address in the future. To read more about open access, see “Reinventing the Academic Journal: The ‘Digital Turn’, Open Access, & Peer Review,” another piece written by Dr. Kelly in collaboration with Dr. Tim Hitchcock of the University of Hertfordshire.

On 22 July 2013, the Council of the American Historical Association (AHA) released its “Statement on Policies Regarding the Embargoing of Completed History PhD Dissertations.” The purpose of the document was to argue that it was in the best interests of graduate students be allowed to “embargo” their dissertations for a period of up to six years. In the document, the AHA encouraged graduate programs and university libraries to follow their suggestions, keeping dissertations offline while the authors could convert the manuscripts into books.

Within hours of the announcement, there were a flurry of blog posts and tweets, and scholars, including myself, took a range of positions — sometimes supportive, sometimes critical. The debates have tended to focus on open access and standards of promotion and tenure within universities. In the weeks that have followed, the debates have been rancorous at times, but the overall conversation has the potential to be quite productive. Among other things, it draws attention to fundamentally important issues that have the potential to transform our profession.

What is Open Access?

Open access is a broad term that describes the principles, practices, and movements associated with the attempt to make information, especially digital information, freely available. For many open access advocates, the desire to share knowledge is a socio-political project. At its core is the the principal of global social equality in which everybody, regardless of background, should have equal access to knowledge.

The idea of open access is not new. The term “open access” was already in use by 1787, when Richard Cumberland argued that the press provided “open access” to “all men.”[1] By 1899, there were discussions over “open access” among librarians in the American Library Association. They debated over whether patrons should have access to books within libraries as opposed to the previous system in which librarians retrieved books on behalf of patrons — and, consequently, put barriers between readers and reading materials.[2]

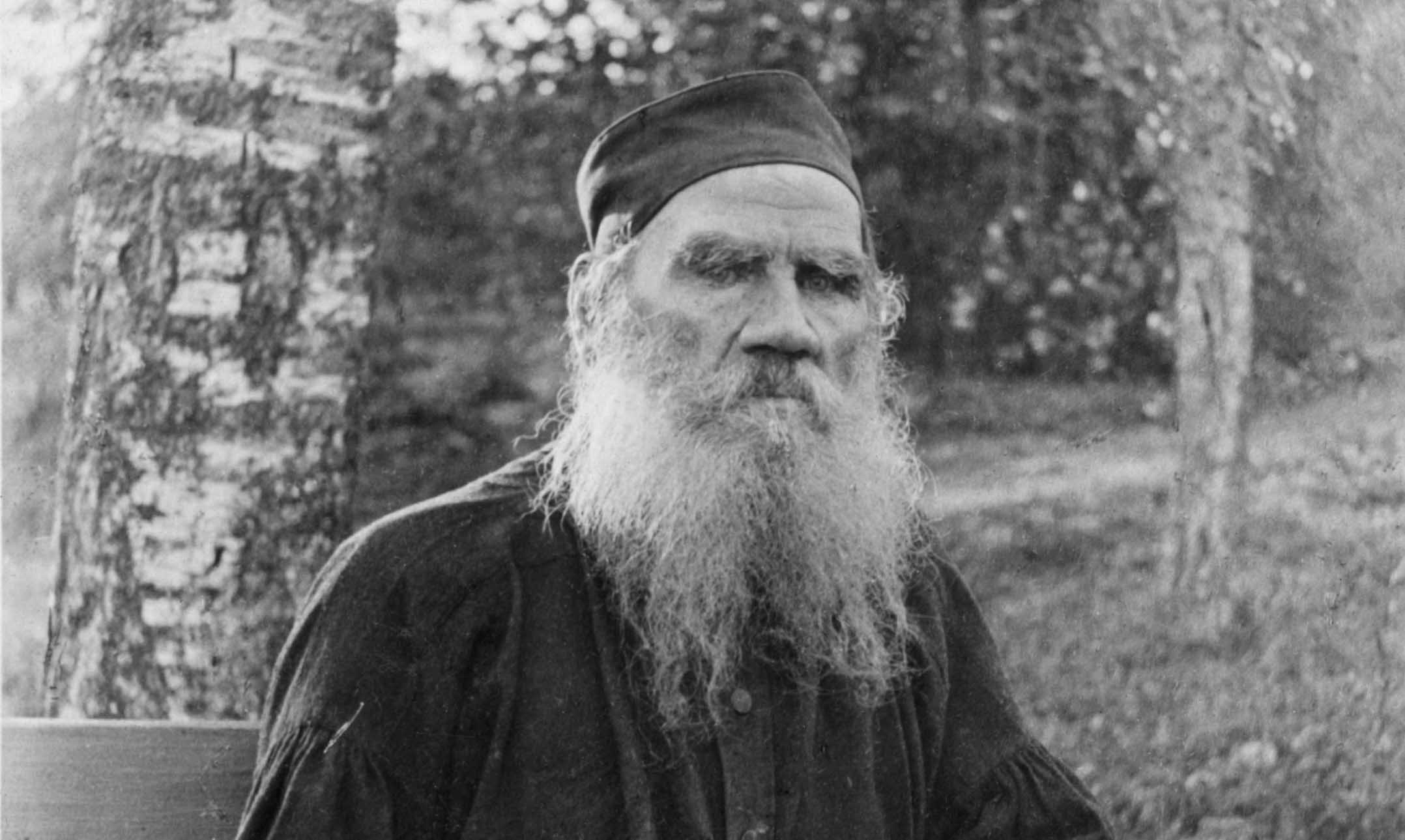

Likewise, the principle that knowledge should be shared freely had early precedents — most particularly among the Enlightenment philosophes. However, the creation of copyright legislation in the nineteenth century sharpened the focus of those who wished for knowledge to be shared freely. This was particularly the case among socialists and other leftists who recognized the democratizing potential of equal education and information sharing. In fact, some writers rejected copyright law and its potential to keep knowledge out of the hands of the working classes. Leo Tolstoy, for example, thanked one of his publishers for printing his work “no rights reserved” in 1900:

“Dear Friends,

I have received the first issues of your books, booklets and leaflets containing my writings, as well as the statements concerning the objects and plan of “The Free Age Press.”

The publications are extremely neat and attractive, and — what to me appears most important — very cheap, and therefore quite accessible to the great public, consisting of the working class.

I also warmly sympathise with the announcement on your translations that no rights are reserved. Being well aware of all the extra sacrifices and practical difficulties that this involves for a publishing concern at the present day, I particularly desire to express my heartfelt gratitude to the translators and participators in your work who, in generous compliance with my objection to copyright of any kind, thus help to render your English version of my writings absolutely free to all who may wish to make use of it.

Should I write anything more which I may consider worthy of publication, I will with great pleasure forward it to you without delay. With heartiest wishes for the further success of your efforts.

LEO TOLSTOY

Moscow,

14th December, 1900 (Old Style).”[3]

These sentiments continued throughout the 20th century. In protest to US copyright laws, Woody Guthrie printed the following on a songbook associated with the Woody and Lefty Lou’sshow on KFVD:

“This song is Copyrighted in U.S., under Seal of Copyright # 154085, for a period of 28 years, and anybody caught singin it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don’t give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that’s all we wanted to do.”[4]

The spirit of Tolstoy, Guthrie, and many other continued through the counter-culture and New Left movements of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. And, early computer programmers picked up on the principles of shared knowledge, though they often stripped it of its political motivations.

One of the individuals whose work emerged out of this milieu was Richard Stallman. Stallman argued that creating what he called “free software” could promote social solidarity.[5] In 1983, Stallman founded the GNU Project, and in the so-called GNU Manifesto, he argued against proprietary software. The GNU project emphasizes four core principles, known as the Four Freedoms:

■ The freedom to run the program, for any purpose (freedom 0).

■ The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

■ The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor (freedom 2).

■ The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.[6]

The Four Freedoms do not guarantee free software, simply the freedom to distribute it and alter it. As Richard Stallman explicated in 1993,

“Free software is software that users have the freedom to distribute and change. Some users may obtain copies at no charge, while others pay to obtain copies—and if the funds help support improving the software, so much the better. The important thing is that everyone who has a copy has the freedom to cooperate with others in using it.”[7]

In other words, while the GNU project stressed openness, it was not anti-capitalist.

While the GNU project focused on software development, the innovations of the internet and the world wide web created the potential to exchange knowledge across the globe within fractions of seconds. With it also came the possibility of making this knowledge freely accessible to anybody with internet access. As in the software design community, arguments began to stress the revolutionary potential of open knowledge. By the late 1980s, a number of open access journals began to be published, and in 1991, arXiv.org was founded by Paul Ginsparg at Cornell. arXiv is a repository and distribution service for science articles, which set the model for numerous other open access repositories.

A conference in 2001, hosted by the Open Society Institute, sparked a number of prominent open access advocates to draft the Budapest Open Access Initiative, which has been a major force in setting the agenda for open scholarship. It defined open access as

“free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited.”[8]

In 2003. this was followed by the Bethseda Statement on Open Access Publishing and the the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities, which emphasized the centrality of open access to research across the disciplines. And, since then, both the movement for open access and the standards and practices of open access have grown and developed.[9] Prevalent in this debate has been concerns over financial matters. There has been a tension between open access and market interests — and debates between liberal and socialist ideological positions — which parallel debates in the free software movement. To what extent should knowledge be beholden to the forces of market capitalism? How does an artist, programmer, or writer make a living by distributing their work in an open access format? In what ways do systems of production and exchange embody socio-political structures? How do systems of open access reproduce or disrupt social inequalities?

The Historical Profession, the Book, Embargoes, and Open Access

Even as many professions and disciplines have increasingly accepted and advocated for the open access model, there have been significant disagreements about its implementation. There are professional practices, economic interests, hierarchies, and traditions, which can undermine the adoption of open access formats. This is certainly the case in the historical profession as the recent flap over dissertation embargoes made clear.

Take, for example, the claim in the AHA statement that “History has been and remains a book-based discipline.” This was an argument used to justify the embargoing of dissertations. It went as follows. First, publishers are reluctant to publish books based on online dissertations (although the evidence is weak on this point). Secondly, many promotion and tenure committees require a book. Therefore, authors should have the choice to keep their dissertations offline for up to six years while the author prepares their book manuscript. The statement is meant to protect the interests of junior scholars, but there are a number of assumptions inherent to the move that reveal the complexity of the situation.

The AHA claim that “history remains a book-based discipline” is embedded in traditions which are rooted deeply in academia. At research institutions, the book is the standard of scholarship. Many justify this perspective by arguing that the work it takes to prepare a book is very different from other research outputs. This is true, but the claim values academic book production over other forms of research. The reasons for their value judgement are vague and lack evidence.

Certainly, not every book is created equal. And, an article such as E.P. Thompson’s “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd of the Eighteenth Century” or Natalie Zemon Davis’s “The Reasons of Misrule: Youth Groups and Charivaris in Sixteenth-Century France” far surpass the scholarly influence of most books. The reasons for privileging the book should be dependent on the needs of the scholar and the audience — not the traditional practices of the discipline.

The academic system has long retained guild-like practices, and the crafting of a book is in many ways equivalent to the apprentice’s submission of a masterpiece to a guild. The object represents expertise, which in turn gives access to a closed society. And, since academic hierarchies are made and sustained through reputation, the book has become a symbolic marker of distinction.

Consequently, the book has in many ways become an end to itself. Rather than creating research outputs that are best suited to content and audience, academic historians must produce a particular kind of object. The effects of this are not inconsequential. Promotion and tenure committees within academic institutions have little impetus to reconsider the markers and measures of academic quality. As such, non-traditional research outputs — including those produced in open access formats, such as blogs, data sets, and websites — are not only devalued, but most promotion and tenure committees have poor measures in place to assess them. It is this, rather than any threat to publishing prospects, that threatens the success of junior scholars who might be eager to produce scholarship in the open access environment. Likewise, the open access movement has much in common with the aims of Public History, a field in which openness and accessibility play a prominent role and in which research outputs diverge from traditional academia. Prioritizing the book over other forms of scholarship reinforces a division between those who produce work for other scholars and those who produce work for and with the public when, in fact, both academic historians and public historians should be producing work for and with other scholars and the public.

But, the book is much more than simply a symbol of scholarly expertise. It is an object at the nexus of economic relations. For academics, the publication of a book is associated with significant financial benefits. For academic presses, the book is associated with significant financial risks. Publishers decide to publish in light of markets, and while academic editors can be essential to developing an author’s ideas, there is always a tension between academic quality and financial efficacy. For publishers, distributing knowledge is still a financial decision, and this means that the information contained in them is a commodity. Those who can pay have access; those who cannot pay do not have access. Wealthy institutions, typically in wealthy countries, have the advantage. Therefore, those in less affluent institutions (and those communities that rely on them), remain disadvantaged.

While it is not at all clear whether the dissertation embargo will be a benefit to junior scholars, it will certainly limit the benefits to their audiences, which in the 21st century increasingly expect (and need) easy and affordable access to knowledge resources. Junior scholars themselves actually stand to benefit from the open circulation of their work. It helps them build a readership and a reputation, and it helps them demonstrate the impact of their work to promotion and tenure committees. Likewise, publishers will stand to benefit by signing book contracts with authors who have an established readership. After all, they are unlikely to benefit from the embargo, which releases dissertations at roughly the same time the book goes to press. And, given the fact that many universities have had to cut back their purchasing budgets, an audience helps guarantee that faculty members will request that their libraries purchase books.

As it pertains to open access, professional organizations, such as the AHA, can do several things that have the potential to protect junior scholars, provide content to wider publics, and sustain scholarship. While many groups, including the AHA, have made statements in support of open access, a deeper intervention into the ecology of knowledge production and exchange is necessary. Creating policies to protect junior scholars from the practices of publishers and tenure committees might best be accomplished through challenging and guiding these committees to reassess and rework their standards and measures. Do these standards and measures encourage the best scholarship? Do they reproduce traditions that might stifle advances in the discipline? How do the standards and measures of tenure and promotion committees reinforce hierarchies and limit alternative models of knowledge production?

Doing so will require a socio-economic critique of the links between institutions, professional organizations, and publishing. Emerging from this critique, there is the potential to align four things: the need to protect scholars, especially early career researchers; the democratizing drive of open access; the desire to improve and expand high-quality scholarship; and the expansion of traditional and non-traditional research outputs that can reach diverse publics around the world.

Note: Since the publication of this essay, two sentences have been modified to clarify the AHA’s position on embargoed dissertations. The AHA has argued that students should be able to choose whether or not their dissertation is embargoed. The original statements said that AHA recommended that dissertations be embargoed.

[1] Richard Cumberland, “No. 43,” The Observer: being a collection of moral, literary, and familiar essays, vol. 2 (London: 1786), 138.

[2] “American Library Association, Atlanta, GA, May 8-12, 1899,” Public Libraries (January 1899):288.

[3] Leo Tolstoy, Patriotism and Government (London: The Free Age Press, 1900).

[4] Dan Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital history: a guide to gathering, preserving, and presenting the past on the Web (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 206.

[5] Richard Stallman, “Why Open Source misses the point of Free Software,” GNU, http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/open-source-misses-the-point.html, accessed 7 August 2013.

[6] “The Free Software Definition,” GNU, http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html, accessed 7 August 2013.

[7] “The GNU Manifesto (1993 edition),” GNU, http://www.gnu.org/gnu/manifesto.html, accessed 7 August 2013.

[8] Budapest Open Access Initiative, February 2002, http://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read, accessed 7 August 2013.